Update #25: Agent Interoperability - MCP, ACP & A2A

MCP, ACP, A2A and many other protocols were created to facilitate agent communication. Let's take a look at what purpose they serve and how they differ

After the rise of MCP in 2024 you would have been forgiven for thinking that we had solved agent communication standards, given how much hype there was around it being the ‘universal agent communication protocol’. However, now in 2025 we have not one universal standard but dozens (yes dozens) of new protocols to solve the same or slightly different use-cases.

Why? Was there something wrong with MCP? We have already seen a ton of MCP servers, clients and use-cases cropping up everywhere so what is the problem? Well, its not a problem with MCP as such, but more a question of vision. Right now, we are connecting agents (sometimes even multi-agent systems) to tools so that they can better do their jobs. Yet the vision of where we will go with AI agents is something much bigger and cooler.

Imagine fast forwarding to where we have thousands upon thousands of AI agents working together, discovering each other, freely sharing information, tackling complex problems, etc. The level of communication required for such a feat would inevitably be vastly more complex, nuanced and varied than in our current use-cases, and that is why we are seeing new and exciting agent communication protocols cropping up all the time.

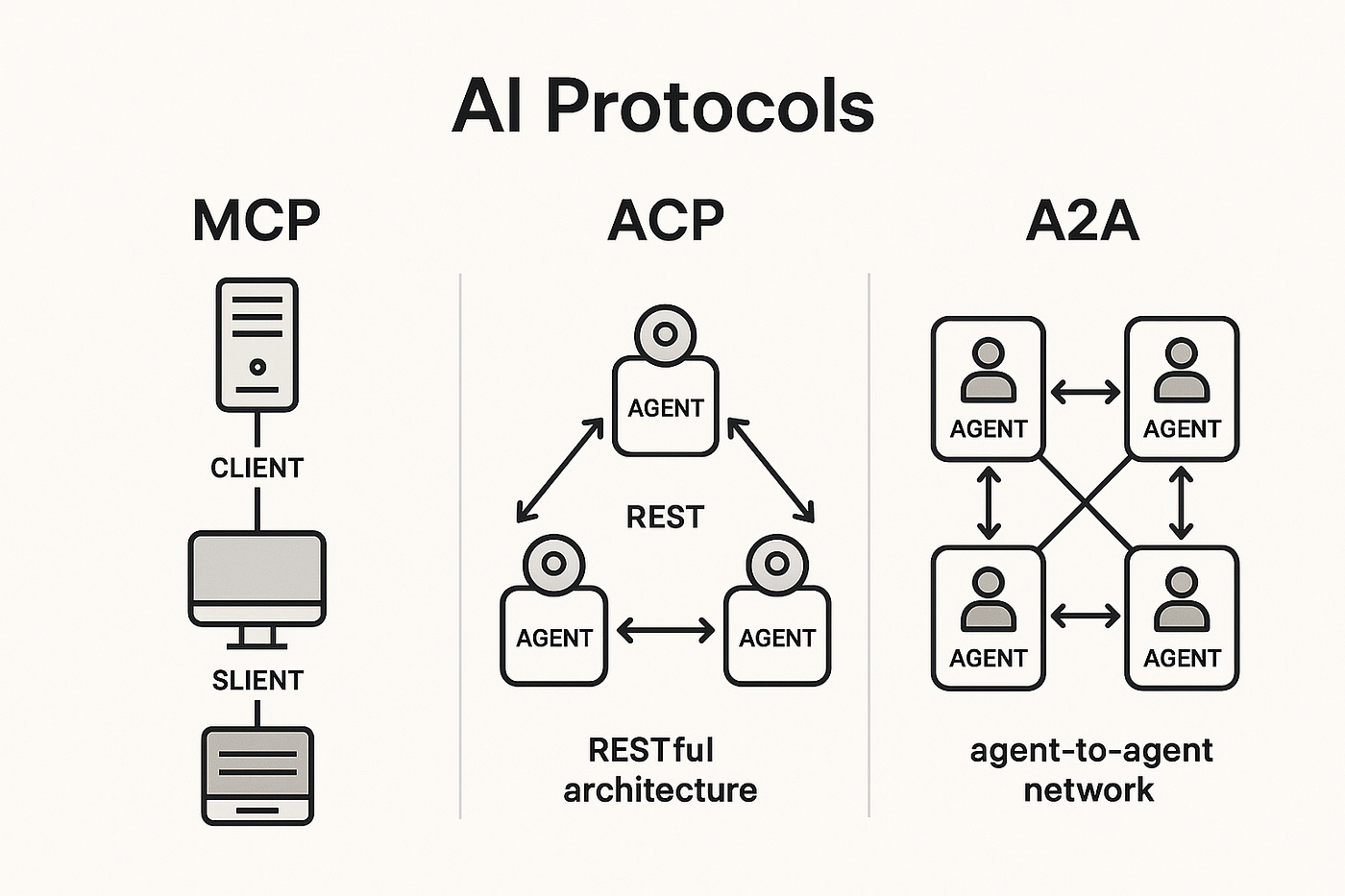

Today, we will focus on 3: MCP, ACP and A2A. These were developed by Anthropic, IBM and Google respectively, showing that this is clearly an area that many of the big players are interested in and actively researching. Let’s get started with the most famous of the lot, MCP.

MCP

MCP, or the model context protocol, was widely regarded as the first and ‘universal’ standard for AI agent communication. It was released in 2024. If you are interested in more of a deep dive into how its client and server communication system works I’ve already covered this in my very first newsletter months ago here. The bit which I am interested in focusing on today is what MCP is designed to do, or importantly not do. MCP is a protocol to connect tools with agents. It standardises how agents access data, tools, external APIs, and context sources. It was designed to stop each individual one of these using custom communication schemas which would very quickly become a headache to manage.

As you can probably start to see when we throw our mind back to the vision of where AI agents will be down the line, this is an incredibly useful and needed standard, but its limited to agent ← → external tools/data. It does not help to solve peer-to-peer agent coordination, task orchestration, handoffs between agents, etc. For these, we have to look further at the other two protocols we’ll be covering today.

ACP

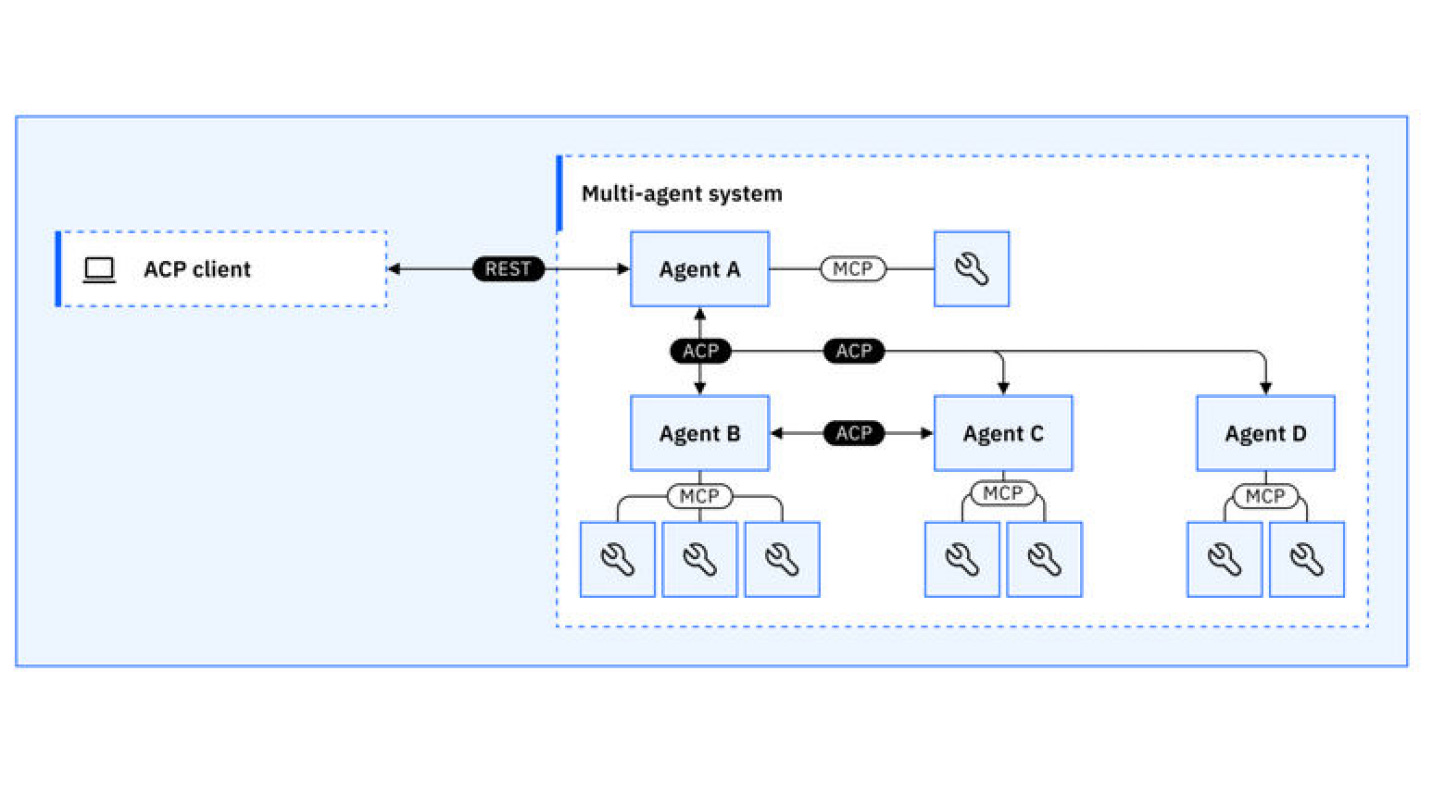

ACP, or the Agent Communication Protocol, already has quite a clear name and goal alignment. If MCP focuses on agents to tool, ACP focuses on agent to other agents. This was created by IBM and BeeAI and is a structured way of letting agents communicate among themselves. By comparison with MCP the elements that are laid out in ACPs communication protocol are more focused on defining a shared language for AI agents to discover, understand capabilities and interact with each other, regardless of their underlying technology or vendor. It allows for the easy sharing of structured data, like text, code, files or media and even to collaborate on tasks.

One of the unique approaches in ACP is the way it structures its communication. Both MCP and A2A use JSON-RPC, whereas ACP follows the traditional REST with standard HTTP verbs (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) making it easy to integrate into existing web infrastructure without specialised libraries. Another advantage of ACP here is that it supports the traditional multimodal messaging inherent to HTTP, allowing for rich structured communication modes using MIME standards. This makes the type of data that can be shared via ACP more varied and extensible than it’s main competitor, A2A.

ACP’s primary use-case is for inter-agent collaboration, allowing easy discovery (even when an agent is offline!) of other agents and allowing them to work together on a single task. Furthermore, this is designed to allow communication of all sorts of AI agents, regardless of their framework, vendor or nature.

A2A (Agent-2-Agent)

As I was researching the differences between ACP and A2A I found some news from the last few weeks that the two of them had actually merged together! I think given the similarity between what they are trying to do and their nuanced differences this is a good thing for everyone. A better communication standard that is the sum of IBM and Google’s research, and less choice paralysis for those of us building agents with these technologies. Nevertheless, let’s cover A2A separately for now as we don’t have a great deal of information regarding their joint-venture long term plans other than the aim will be to incorporate ACP into A2A.

For all intents and purposes the A2A protocol is trying to solve the same problem as ACP: inter agent communication standards. It’s Google’s attempt at enabling agents built by different parties to talk, share tasks, and coordinate in a distributed and vendor agnostic way. One of the differences to ACP here is that it uses JSON-RPC 2.0 wrapped in HTTP POST requests, meaning that you need to understand and work with both. This is highlighted as an area where ACP’s approach is notably simpler and easier to use, so is likely an area that will follow ACP’s REST HTTP route in the merger.

Another area where ACP and A2A differ is in their communication model. ACP uses the more traditional client-server style of communication, whereas A2A uses peer-to-peer decentralised models which simplify architecture.

Discoverability is also different with A2A. Whereas ACP focuses on agents ‘registering’ themselves within an ACP environment, A2A uses the concept of ‘agent cards’. These are JSON files at easily-findable locations which describe the agents capabilities and endpoints, allowing for dynamic discovery across platforms and networks.

Conclusion

Diving into this topic has been a very interesting way of gauging how the big players are thinking about the future of AI agents. Why would so many big name companies be dedicating large amounts of resources to understand and create these sort of protocols if they didn’t believe that AI agents were headed for a far more widescale, distributed and rich adoption and usage. It’s one of those interesting scenarios where the technological evolution is foreshadowing the next chapter of our AI agent adoption, which I find fascinating.

It is also very useful to understand this stuff at a lower level for what we are building here at Secure Agentics too, as this feeds directly into conversations that I am having on a daily basis. For now that is everything, thanks and catch you next week!